Introduction

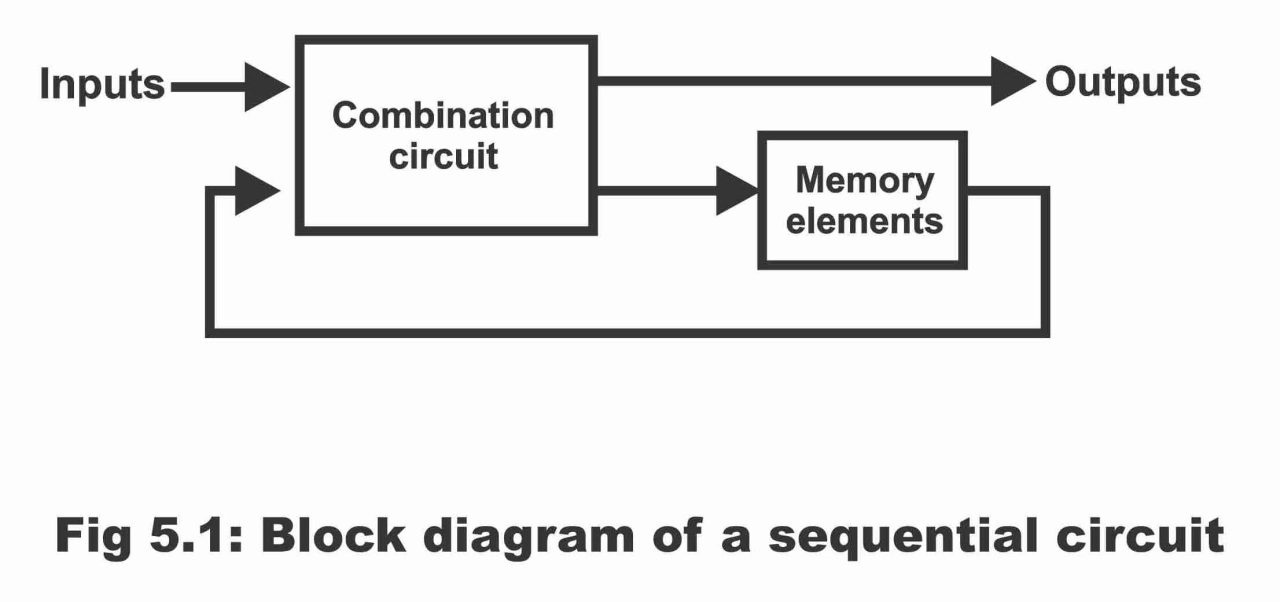

Sequential circuits are digital systems that remember past inputs in addition to processing current inputs. They combine combinational logic with memory elements (latches/flip-flops) so that outputs depend on both present inputs and stored state. This “state” or history dependency distinguishes them from combinational circuits, which have no memory and whose outputs depend only on current inputs. In practice, sequential circuits require timing (clocks) to control when states update:

Synchronous sequential circuits use a global clock; all memory elements update together on clock edges.

Asynchronous sequential circuits have no central clock and change state immediately on input changes, but are harder to design reliably.

Figure: A sequential circuit includes combinational logic and memory. The outputs depend on current inputs and previous state (via memory elements).

In summary, sequential circuits use memory elements (like latches and flip-flops) to store bits and implement state machines, counters, registers, and other devices. Their outputs depend on both inputs and stored state. This makes them essential for designs like CPUs, digital watches, communication devices, and control systems.

Key differences with combinational logic (from GFG):

Dependence on history: Sequential outputs depend on current inputs and past states.

Memory elements: Require flip-flops/latches to store state.

Clocking: Synchronous sequential circuits use a clock signal to time updates; combinational do not.

Examples: Combinational – adders, multiplexers; Sequential – counters, shift registers, state machines.

Feature | Combinational Circuits | Sequential Circuits |

Output Dependency | Only on current input values. | On current and past input values. |

Memory | No memory elements are present. | Memory elements (latches, flip-flops) are essential. |

Feedback Path | No feedback from output to input. | A feedback path exists to store state. |

Timing | Asynchronous; outputs change immediately. | Can be synchronous (clocked) or asynchronous. |

Examples | Adders, Multiplexers, Decoders. | Registers, Counters, Finite State Machines. |

The Role of the Clock in Synchronous Systems

The clock signal is a central, periodic timing pulse that serves as the organizing principle for synchronous sequential circuits.

Its primary function is to create predictable, orderly behavior by ensuring that all changes in the circuit's state occur at precisely the same moment, on a specific clock edge. This prevents a chaotic cascade of changes and allows for reliable, multi-stage data processing.

A "clock domain" is defined as a collection of flip-flops that are all driven by the same clock signal. In modern VLSI systems, it is practically impossible to distribute a single clock perfectly across a large chip without experiencing delays and distortions.

This physical reality is why chips are increasingly designed with multiple, independent clock domains. This necessity for multi-clock designs, in turn, gives rise to more complex challenges like clock domain crossing (CDC) and metastability, which are critical topics for advanced VLSI engineers.